(Family of Franziska Pedersen, Canada)

The Yugoslavian government decided to put all of the German people of Yugoslavia into concentration camps. Soon one day at 4:00 a.m. the army knocked on our door and said, “We will give you ten minutes to take what you can. Leave the rest.” Mother and Father had us three little girls to dress. Mother asked, “Are we coming back?” to which the soldiers replied, “No.” Mother told Father to pack as much of the girls’ clothes as he could. She took some bread and milk, and then time was up. We were put in a wagon pulled by horses. They closed half of our village Jabuka off with barbed wire, put a gate, and placed a guard there; that is where everyone was brought to live. No one could get in or out. Most of the people were elderly or mothers with children. All the younger ones and those who were able to work were taken to a different location to work for the government. As soon as we left the house, a seal was put on our door that said, “Government Property.”

Our Mother, with us three girls, Theresa, Barbara, and Franziska and our cousins (our mother’s brother Wendel’s boys), Bernhard and Michael were with us, and Oma Janko (grandma Yanko)—our mother’s mother. In this camp was a community kitchen where we all had to get our food. Our aunt Eva, Uncle Wendel’s wife and mother to Bernhard and Michael worked in the kitchen for the police at that time. She was allowed to remain in the village, outside the camp.

One week after our family, together with many others, had been put in the camp, our Father was walking with several other men with a soldier watching them. They were carrying bags of salt on their shoulders, when a jeep came along and stopped. Peter Cosic got out of the jeep and stopped the men, but the soldier said he was not allowed to speak with the prisoners. (Remember, Peter Cosic was the spy for the Partisans, whose false passports Father had found but did not turn in to the authorities, and who later took Father across the river).

Peter said to the soldier, “This man is not your prisoner. I am taking him with me,” and then he showed his ID. Peter told Father to put the bag of salt down. He then told the soldier to pick up the salt and take it with him. Peter took Father to the headquarters where he told him to wait in the first room, while he went into the next. Father said that there was a lot of loud talking going on, but finally Peter came out with a document in his hand and said, ”Let’s go get your family. You are free to go home. I got your house for you and everything in it.” They had a soldier go with them and they had to show the documents that Peter gave to many different officers on the way, and finally they got our Mother and us girls and we went home.

When we got home, our clothes, the bedding, the chickens and horses were gone. Our neighbour had heard the animals get restless when there was nobody there to look after them. When he went over to see what was happening, and saw the sign on our door, he decided to feed the animals and take care of them. In the evening he and his son took the horses to their property to make it easier to look after them. We also got our clothes and bedding back.

Life was not too bad for a few months. Father and Mother had ID cards which were good, but of course they stated that we were German and in those days one had to show the ID cards practically daily. The Police made checks on the buses, trains and in the stores, or when just walking in the village. Usually several times a day they had to explain their situation because it was common knowledge that Germans were in camps.

Many times, they came to get Father to force him to work on the Sabbath. One Friday night, Father was tied up, hands and feet, and thrown in the corner behind a door in the town hall. The door flew open very early in the morning and Peter Cosic walked in. When he saw Father, he said, “What are you doing here? “Father said, “I am waiting for the transport truck to come get me.” That was the way they collected people and took them out of town to be shot. Peter went through the door and after a while, someone came out, cut Father loose and said, “Go home.”

This freedom did not last very long. About six months after being allowed to go home from the camp, the soldiers, rifles in hand, knocked at our door one evening, “Open up,” they shouted. They stormed in and collected everybody, put us on a wagon and took us back to the concentration camp. They accused us of harboring Germans at night and giving them food. Sometimes young mothers would get away from the camp and beg for food for their children. Of course our parents would help as much as they could. The soldiers went to the pantry and took out what they liked. They said, “If you can show us the receipt from the store, we will let you keep it.” That was the beginning of three years in the concentration camp. Peter Cosic had been transferred to another area, so he did not know what happened to the Polzer family. Thank the Lord that Peter Cosic had been able to intervene for our Father so many times and save his life more than once.

After a few days in the camp in another area of our village Jabuka, where we had been before, everyone was rounded up and we walked about 14 km north-east to a railway station at Kacarevo (Kacharevo). Beside this railroad station was a brickyard; it was a very low area; we were all made to go down there and the guards were above us with their machine guns, ready in case someone would try to run away. Our oldest sister Theresa thought this was the place they would kill us all. She prayed to God that if they did it, please let us all die quickly with the first bullet and without pain. Thank God, it did not happen. It was not our time yet to die. The Lord had again intervened.

Later we were all put into box cars—120 people in each car. There was standing room only. The train travelled all night and on the following morning we arrived in Knicanin (Knichanin), a large town fenced in by barbed wire, with a gate and guards at the gate.

In 1945 the authorities of the new Communist Yugoslavian government made the former ethnic German community of Rudolfsgnad into a massive concentration camp and renamed it Knicanin. This concentration camp was the largest of the eight camps for ethnic Germans (‘Donauschwaben’), active from 1945 to 1948 in what is now modern Serbia. Most of the inhabitants of Knicanin had been evacuated with the retreat of the German forces and the Russian army advancing, but the town was severely damaged during the battles raging around it by the military. Those brought in the box cars were put into the ruined or damaged empty houses. Our Mother, we three girls, our Grandmother Janko and her husband Johan (our Grandfather), and our cousins Bernhard and Michael, were again together in a house, as well as some other people. We slept on straw on the floor with a walkway through the middle with a total of 18 people in the room.

There was nothing to eat, so we went to look for vegetables in the garden, but found nothing. There were some large kettles found in one of the buildings to cook for the people, but the only thing we got to eat were dry peas and corn groats infested with bugs—no salt, no oil, and often no bread for weeks and months. Sometimes cooking was done only every third day, so we ate dandelions, grass, and all kinds of greens that we could find. There were days when the rations were reduced or no rations given at all which only heightened the level of starvation in the camp. Those who were able were sent outside the camp to work. If they found some food and tried to smuggle it back into the camp, the food was taken away from them and they were punished.

The resistance to disease was very low as a result of malnutrition and starvation and so there were many health problems in the camp such as infections, rashes, typhus, diphtheria and diarrhea which also contributed much to weakness. There was absolutely no medical help either. People died every day. Most of the victims were women and children as most of the men had been shot earlier.

At first Father was not in this camp with us. He had to stay with the working class back in Jabuka and things were not going well in our village back home. Every morning all the men had to stand at attention and get their assignments. Although all the officers knew that our Father would not work on the Sabbath, they brought him tools and commanded him to get to work. One Sabbath they told him to get a tree stump out. Father said, “It is the Lord’s Sabbath, and I will not do it.” They then took him to the basement of that building and beat him very badly. Then they said, “Ok, get out there and get that stump out.” So he began walking up the steps staggering and spitting blood—some of his teeth fell out. At that time an officer arrived in a Jeep and looked at our Father. The officer asked the soldiers, “What is this?” and went inside with them. Father remained standing at the steps. His fellow townspeople said, “Josef, why are you doing this? It would not kill you to take that stump out.” He said, “This is God’s Sabbath. If I did it, the communists would say, ‘I am your god and you better do what I tell you to do.’” After that Sabbath, they left our Father alone in the barracks and nobody tried to force him to go work anymore on the Sabbath.

Back in Knicanin where Mother was with the children and grandparents, things were not going well. Within six months, most of the people in our house had died of starvation and disease. Every morning, those that were still alive had to take the dead out, wrapped in blankets and place them on the sidewalk. Some men on a wagon pulled by horses came through the street to collect the dead bodies and take them out of town to bury them all in a mass grave. Our Janko Oma and Opa (our mother’s parents) also died in Knicanin. The houses were infested with rats which at times chewed on those who had died during the night. Mother was six months pregnant with our brother Josef, and Franziska was 2 ½ years old; so Mother had to watch us at night so that the rats would not bite us. Hunger was so great that some people even ate their pets. While we were in this camp our cousins’ mother Eva, who was working for the police in the Jabuka area, having connections with people of power got permission to get her two sons out of the camp.

Father ran away from Jabuka one night; he wanted to be with his family, our Mother and us girls. He walked all night and day and came to be with us in Knicanin, about 50 km north-west of Jabuka. He had to sneak in through the fence at night. He made it through all right.

While in this camp, the Polzer family met Sister Juliana Bauman, her sister Barbara and their five children and grandmother Gebhard, a family of eight. After becoming acquainted with them, they studied the Bible with Father and then became members of the Reform Church.

God was good to our family. There was a brother from the SDA Reform Church, Br. Velimir Jankic; we called him Cika Velimir, (Uncle Velimir). He was Nicola Sattelmayer’s uncle (his mother’s brother). Sometimes Cika Velimir came walking, carrying on his back a knapsack full of food for the Polzer family. Uncle Velimir lived in Besni Fok about 33 km south of Knicanin. He always had to have some extra food for the guards; otherwise, they would not let him into the camp to bring us the food. Sometimes, the members of the church let him have their wagon and horses, so he did not have to walk. The food from Cika Velimir kept us alive. Out of the 18 people in our house, 10 died, and that is how it was throughout the whole camp.

One day Cika Velimir asked our parents if it would be OK to take our sister Theresa home with him. They agreed. She had to put on a disguise and go through the gate at the camp with the ladies who looked after the cattle outside the camp. She got out ok. Cika Velimir was waiting at the main road to the next town. They had to walk many kilometers, plus take a truck ride until they got to his home in Besni Fok. Theresa got very sick with scarlet fever and almost died while with Brother Velimir. He took her to the doctor and took good care of her, and she got well again. She remembers that she had lost so much weight that her shoes fell off her feet. She loved staying with Brother Velimir. He also had a lady and two young men who had run away from the army hiding out at his house. Once Theresa had recovered well he brought her back to us into the camp at Knicanin. Theresa was hiding under a blanket in his wagon. He told Theresa that while he spoke with a guard around the corner of the building, she was to get out from the wagon and crawl through the hole in the fence, which she did.

While away from our parents for almost a year, Theresa also spent some time with another young couple, who had no children, but she was not very happy there. And then one day one of the elders from the church came. He was a friend of our family; it was Br. Djura Milic. He asked Theresa whether she liked it with this couple. She began to cry. He then asked her if she wanted to go stay at the Jelovac’s house. The Jelovac family were also members of the Reform Church. They lived not too far from Uncle Velimir. They had a girl, Mara, and Theresa was good friends with Mara. Theresa was very happy and went to stay at Mara’s for a while. At Jelovac’s she met Peter, Dusan, and Ivanka Sattelmayer; they were Brother Fritz Sattelmayer’s children.

During this time our brother Josef was born in Knicanin in January 1946. He did not have cow’s milk until he was 2 ½ years old. Mother nursed him for a long time, but that was very hard since there was not much food for her to eat.

Officially, over 11,000 Germans died in this camp by starvation, disease and execution by the communists led by Josip Tito, who ruled after the Nazis were defeated. Theoretically, however, the numbers of German victims was much higher due to the thousands that were sent to the Soviet labour camps. All ethnic Germans were treated as war criminals, despite the fact that a very low percentage of them sympathised with the Nazi party.

In 1947, rumours were going around that all the men and their families were going to be sent to Serbia to the coal mines. Father told us we had to get out at once. If we were taken to the coal mines, there would be trouble because of working on Sabbath, plus his health could not take working underground. There were ladies who got out at night to look for food, and one of the ladies offered to take our family and some friends past the guards and barbed wire at night.

One day, we all got ready to flee the camp. We packed all the belongings we had (which were very few), had prayer with some friends and then sneaked out in the dark, very close to the guardhouse. It was January 1948, and it had snowed during the day. The snow was frozen and our walking could be heard. We crouched under the fence close to the guardhouse. There were three or four guards in that little house trying to stay warm, smoking cigarettes, talking and laughing loud, so they did not hear us going by. God had surely sent His angels to protect us, because on the other side of the fence was an open field, white with snow and the moon shining brightly. It was almost like daytime, and none of the guards saw us.

We walked all night and had to cross a few rivers by rowboat. At daybreak, the lady who was our leader took us to a guardhouse. She knew the people there already from other trips. They were kind and put us up in the stable on clean straw. She gave us breakfast of cornmeal porridge with milk, and that was the first time our brother Josef had milk to eat. During that night, the walking had been so hard on our feet. We had no shoes with hard soles, only some handmade slippers that our mother had knitted out of wool. She undid Father’s sweater and made slippers for us children. The soles were made of several layers of old fabric. Theresa was 11 years old, Barbara was 8 and Franziska was not yet 5 (4 years and 3 months). Father had to carry Franziska all night on his neck or back, sitting on top of his knapsack. Mother had a kerchief tied around her neck hanging down to the front over her shirt, and that is where little Josef was laying. Sometimes because the ground was frozen and slippery, mother would fall and Josef started to cry. In the night, you could hear sounds very far, but thank God, He kept us safe. Mother would tell Josef, “Soon we would get some kulja (cornmeal porridge) and milk to eat,” and that kept him quiet again for a little while.

The next day, we started out to walk some more to go to Besni Fok to a family from the church, the Jelovac family. They had a big farm and a little house. We walked all afternoon and at night sometime around 10:00 p.m., we arrived there. They had four or five big dogs, and they came to meet us quite far away from the house, barking very loudly. Theresa knew the dogs by name and called them. At first, they did not trust to come near because there were so many of us, but then the old dog came to Theresa and she petted him and called the others by name. After a while, they walked with us to the gate, but seeing that we were going into the yard, they started to get mean and bark loudly, so we stopped. Zdravko, one of the boys, came out telling the dogs to stop and asked who was there. Theresa said, “it’s Lepa (a nickname she had) and my family.” He could not believe it. He opened the door to the house and yelled, “The Polzers are here!” They all knew we were in the concentration camp.

We stayed in that area for six weeks with Cika Velimir; he lived not too far from the family Jelovac. While there we put a little weight on and got all new shoes and clothes and got ready to take a train trip to Slovenia towards the German border. There were people there who had a vineyard on the border of Austria and Germany. They helped many people get across the border

by night. After six weeks, Cika Velimir and Maria (the lady who was our guide) came, and we all started out for Germany. On the train trip it was not easy because Franziska, Barbara, and Josef did not speak the Serbian language, so they always spoke with our parents in German, and the passengers stared at us. That was dangerous because at any moment somebody could have told the conductor that we were a German family and we could have been arrested. But all went well all day long and we got out of Serbia Bocho into Slovenia.

In the afternoon, we arrived in a city called Sombor (Zombor). This was about 200 km north-west of Jabuka, near the Hungarian border. There we had to get off the train and wait in the station for two hours to catch another train that went to Slovenia which was close to the Austrian border. We sat on benches, and Cika Velimir and Maria went to look for food. After half an hour, a policeman came to look at everybody and recognized our Father from the concentration camp because Father had worked in the vegetable gardens and delivered vegetables to the guard’s station. The policeman did not say a word, but just left. Fifteen minutes later, he came back with two more officers and just said, “Okay, Polzer, get your family together and come with us.” So they took us to the camp in that town, Sombor, about 180 km north of Belgrade.

When Cika Velimir and Maria came back, they arrested them. We do not know what happened to Maria later on. Cika Velimir was in prison for one year. He never told us that, but his sister Dara, Nicholas Sattelmayer’s mother, told Theresa years later when both Theresa and Dara, with their family, lived in the USA, that Cika Velimir went to prison for helping us.

Compiled by, Franziska Pedersen

To Be Continued next month.

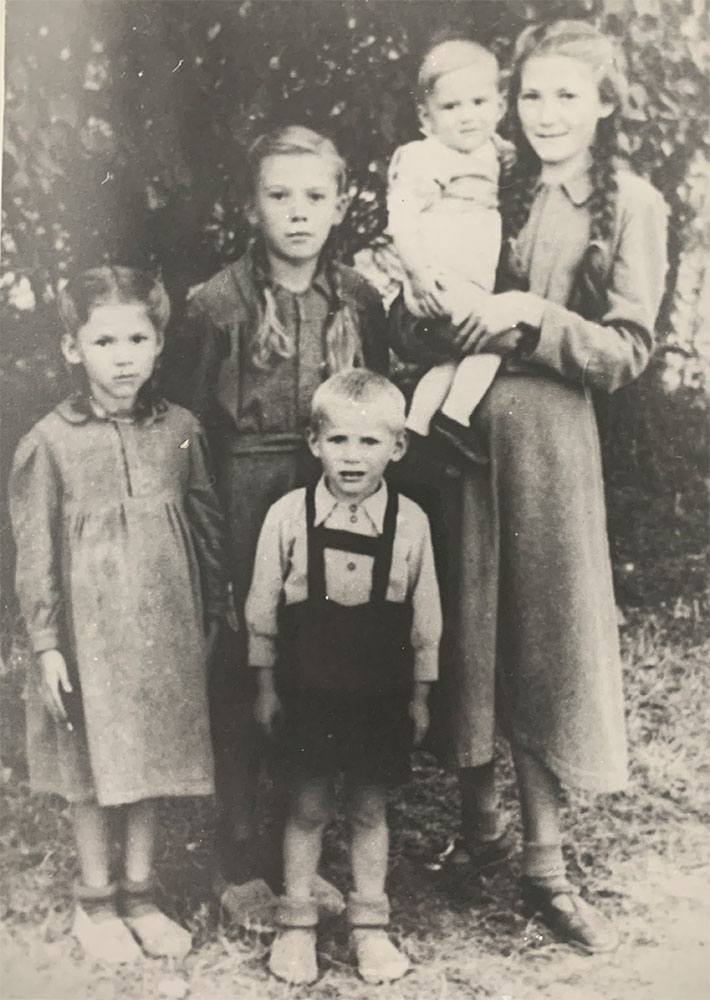

Coming up: Events during and after the Concentration Camp. Photo below taken in 1950, in Jabuka, two years after being released from the concentration camp.